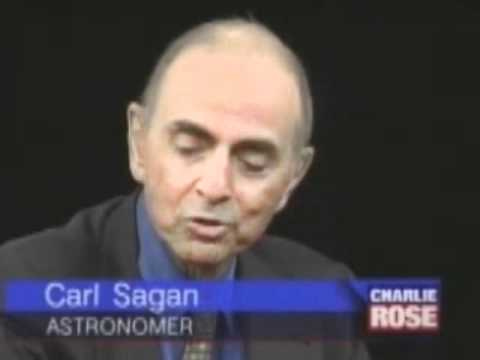

Carl Sagan was an American astronomer, astrophysicist, and science communicator who made significant contributions to popularising science and advancing the field of astronomy. Sagan was widely known for his ability to explain complex scientific concepts in a way that was accessible and engaging to the general public.

Throughout his career, Sagan conducted extensive research in planetary science, particularly on the study of extra-terrestrial life and the possibility of life beyond Earth. He played a prominent role in various space missions, including the Mariner, Viking, and Voyager missions, and he contributed to the development of the Golden Record, a message from Earth carried by the Voyager spacecraft.

Apart from his scientific endeavours, Sagan was a strong advocate for critical thinking, scientific scepticism, and the importance of evidence-based reasoning. His enthusiasm for science and his ability to convey the wonders of the cosmos to the public left a lasting impact on the popular understanding of science and inspired many individuals to pursue careers in scientific fields.

Whilst I whole-heartedly agree with his evidence-based reasoning, and of course the need for critical thinking, I think it is also important to remain more open to concepts that science has so far dismissed or not yet touched on (and perhaps never will). Nevertheless, Sagan was a formidable thinker.

Carl died in December 1996. The following excerpts are from his last interview in May 1996.

“We live in an age based on science and technology, with formidable technological powers. Science and technology are propelling us forward at accelerating rates, that's right. And if we don't understand it - by "we," I mean the general public - if it's something that, "Oh, I'm not good at that, I don't know anything about it," then who is making all the decisions about science and technology that are going to determine what kind of future our children live in? Just some members of Congress, but there's no more than a handful of members of Congress with any background in science at all.”

“There are two kinds of dangerous. One is what I just talked about, that we've arranged a society based on science and technology. There was nobody who understands anything about science and technology, and this combustible mixture of ignorance and power sooner or later is going to blow up in our faces. I mean, who is running the Science and Technology in a democracy if the people don't know anything about it?

And the second reason that I'm worried about this is that science is more than a body of knowledge. It's a way of thinking, a way of sceptically interrogating the universe with a fine understanding of human fallibility. If we are not able to ask sceptical questions, to interrogate those who tell us that something is true, to be sceptical of those in authority, then we're up for grabs for the next charlatan, political or religious, who comes ambling along. It's a thing that Jefferson laid great stress on. It wasn't enough, he said, to enshrine some rights in a constitution or a Bill of Rights. The people have to be educated, and they have to practice their scepticism and their education. Otherwise, we don't run the government; the government runs us.”

“The thing about science is, first of all, it's after the way the universe really is and not what makes us feel good. And a lot of the competing doctrines are after what feels good and not what's true.”

“Let's look a little more deeply into that. What is faith? It is belief in the absence of evidence. Now, I don't propose to tell anybody what to believe, but for me, believing when there's no compelling evidence is a mistake. The idea is to withhold belief until there is compelling evidence, and if the universe does not comply with our predispositions, okay, then we have the wrenching obligation to accommodate to the way the universe really is.”

“Religion deals with history, with poetry, with great literature, with ethics, with morals, including the morality of treating compassionately the least fortunate among us. All these are things that I endorse wholeheartedly. Where religion gets into trouble is in those cases where it pretends to know something about science. The science in the Bible, for example, was acquired by the Jews from the Babylonians during the Babylonian captivity of 600 BC. That was the best science on the planet then, but we've learned something since then.”

“The trouble comes with people who are biblical literalists, who believe that the Bible is dictated by the creator of the universe to an unerring stenographer and, therefore, has no metaphor or allegory. And from there, they make their political, economic, and social choices.”

“Professor Mack, John Mack, is a professor of psychiatry at Harvard who I have known for many years. We were arrested together at the Nevada nuclear test site, protesting U.S. testing in the face of a Soviet moratorium on testing. And many years ago, he asked me what was there in this UFO business, is there anything to it? And I said, absolutely nothing, except of course, for a psychiatrist. Well, he looked into it and decided that there was so much emotional energy in the reports of people who claim to be abducted that it couldn't possibly be some psychological aberration, that it had to be true. He believed his patients. I do not believe his patients.”

Sagan was a puppet for the beast system hypnotising us in to thinking we are insignificant cosmic accidents in an infinite godless universe. Neil Disgrace Tyson & Brian Cock are his nauseating replacements

When I was younger and Sagan was still around I enjoyed seeing him on Carson. After he died I never thought too much about him until a year or so ago when someone I know suggested I read one of his books, the title escapes me, so I checked it out from the local library.

The book opened with Sagan describing a trip he was on. He was leaving an airport to go to his hotel, I think that's where he was going, and he got into a cab. He said the driver recognized him, asked if he was Sagan and Sagan said yes.

The driver then said his name was William Buckley, I think that was his name, and they had a laugh over that. Then the driver engaged Sagan about a few topics, the lost city of Atlantis was one, and on each topic the driver was excited about the possibilities each topic was based on ancient fact. Each time Sagan, being the wise person he considered himself to be, shot down the driver's enthusiasm down by saying no, the topic wasn't true.

That's a rough paraphrase of the opening of the book. After reading that I thought if Sagan was a true "scientist" he would have joined the driver in his enthusiasm by saying something similar to "we don't have evidence that Atlantis existed but we should keep looking ...". Instead he basically said "no", Atlantis didn't exist.

I quit reading the book because I concluded Sagan was little more than an arrogant charlatan.