The following is part of a post by The Consciousness of Sheep. I have removed the beginning of the original post because it discusses the decline of British seaside towns which might not be of interest to international readers.

I think this section on London could apply to any major Western city and details why the decline in prosperity we are experiencing is becoming increasingly visible. You may not agree with the energy cost of energy theory but you can’t deny how far many cities have descended in the space of a few years. Already we have seen major UK cities declare bankruptcy with surely many more to come.

London – even formerly prosperous central London – is displaying all of the symptoms of decline which were so obvious in places like Blackpool a generation ago. And while it is tempting – and psychologically necessary – to blame Covid, the war in Ukraine, and even Brexit for the collapse of what was once Europe’s most valuable retail district, the roots go much deeper.

The UK’s antiquated system of local business rates is the primary reason why so many stores are closing. The system taxes businesses according to the value of the property they are in rather than their annual profits. And in central London, that can leave businesses with a bill for more than £100,000 just for being there. On top of that are the higher wages in London, along with increasingly high electricity prices.

Less obviously though, businesses are being drained by a profligate London authority which, like so many of the UK’s local authorities, has been permitted to rack-up huge debts while inventing ever more ways to fleece local businesses and households to pay for it all. Even this though, is merely the local government dimension of a far deeper surplus energy crisis.

The reason I was able to point to Blackpool as London’s future six years ago was not due to clairvoyance or astrology. Rather, it was due to an understanding of what must happen to an import-dependent economy in a debt-based financial system when the available surplus energy goes into reverse.

In our debt-based economy, almost all of the currency we use comes in the form of bank credit – the numbers which appear on your bank statement – which is created every time banks make loans. But nobody borrows currency just to look at it. When we – businesses and households – borrow currency, it is either to invest or to purchase goods and services. But banks don’t lend currency just because businesses and households want it. Banks only lend currency that they can make a profit from… something they judge by assessing the credit-worthiness – i.e., the ability to repay – of the businesses and households seeking credit. For we mere mortals, this means our wages. But for businesses, it also includes forecasts of the likely profitability or otherwise going forward. And this can affect our access to credit too, for example if the bank judges that the business we work for is at risk of failing.

The problem – as we saw in the 2008 crash – is that this can become a self-fulfilling prophesy, since if banks cease lending, the amount of currency in the system falls, creating a recession and even a full-blown depression. Ironically – again, as we saw in 2008 – when the banks make too many loans, there is so much currency in circulation that it appears that even the least reliable business or household will be able to repay its loan. But when there is too little currency in circulation, even good businesses and households can rapidly find themselves underwater.

Credit/debt is where the two parts of the economy – real and financial – come together. When a bank assesses the likelihood of a business repaying a loan, it is, in effect, calculating the odds that the business can maintain and increase its productivity so as to repay the debt with interest. And for the most part, when businesses seek loans it is precisely to invest in technology to increase productivity (except in privatised monopolies and glaserised businesses, where shareholders simply borrow their dividends and then leave the customer on the hook to repay the debt).

As the energy cost of energy has risen since the 1970s, productivity gains – using technology (in the broadest sense of the term) to maximise the proportion of energy converted into useful work (exergy) – have been increasingly difficult to secure. In previous eras when this occurred, developing new, more energy-dense and versatile energy sources provided the way forward… for example, turning to charcoal to replace wood for heat, and waterpower for horses for motion, followed by the transition to coal and the later transition to oil and electricity. But for the moment, we remain stuck with oil as our primary energy source, with the proposed alternatives so under-powered that they can only make the productivity problem far worse.

Problems arise as energy-intensive industries cease being able to increase productivity. Starting with the old, coal-powered industries of the nineteenth century, this is precisely what has been happening in the UK since the 1950s (and to some extent since the end of the First World War). For strategic reasons, governments of all persuasions sought to maintain critical industries like coal mining, steel working, ship building and railways, having just recovered from a war which highlighted the necessity of them. And as the UK enjoyed the prosperity of a post-war economy making the switch from coal to oil as its primary energy, government could recover enough taxes to subsidise these nationalised industries. By the 1970s, with the switch to oil ending just as the more expensive OPEC era was beginning, productivity slumped.

This is not to suggest that what followed was inevitable or that more rational options were not available. It is simply that from the mid-1970s, UK governments of both colours turned to neoliberalism as the “solution” to what they did not realise was a fall in the surplus energy powering the economy. And central to the neoliberal project was the undermining of workers’ wages, which usually appear as the largest cost to a business. This was achieved by generating a reserve army of labour by bringing far more women along with migrant and domestic minorities into the workforce under the auspices of equalities legislation, the offshoring of energy-expensive industrial processes to regions of the world with cheaper labour and fewer regulations (workplace and environmental) and by sustained attacks on trade unions and economically left-leaning political parties.

It was the UK’s good and bad fortune that coinciding with the shift to neoliberal economic policy came the once-and-done boom in oil and gas from the North Sea. A hydrocarbon boom which provided the basis for the massive expansion of the City of London Ponzi racket to the point that by the turn of the century every British household was being indirectly subsidised by the casino activities of the bankers. To our great cost though, the political class chose to believe that the debt-based boom was down to the success of their policies rather than being a big ugly financial bubble waiting for a pin.

Ultimately, neoliberalism’s problem was one identified by Karl Marx a century earlier – the “crisis of over-production” – although in the modern economy it manifests as a crisis of under-consumption. Driving down workers wages may have appeared to work. And since it often had a geographical dimension, those who enjoyed the prosperity that remained could convince themselves that all was well, while playing the age-old game of blaming the victims. But by the early 1980s, Britain’s ex-industrial regions were joining rundown seaside towns like Blackpool in a process of decline as the currency required to maintain the local economies disappeared. Empty factory buildings and boarded up shops sprouted like mushrooms, particularly across the north and west, where the heavy industries of the Industrial revolution had grown up.

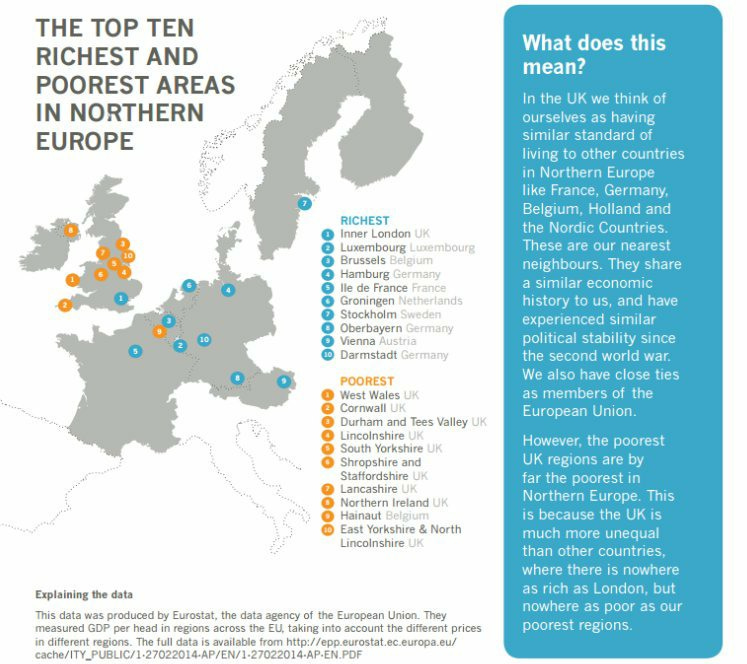

But even this “north-south divide” was not the end of it. By the early 2000s, prosperity had retreated even further. London, along with the top-tier university towns, remained among the most prosperous places in Europe. But alongside them, the UK contained nine out of the 10 least prosperous regions of northern Europe:

Again, barring a rise in wages which requires increased productivity which, in turn, requires a new and yet-to-be-discovered energy source, this process – like ageing – does not stop. London is no longer the prosperous centre that it was a decade ago. Sure, the process has been accelerated by two years of lockdown and the self-destructive sanctions on Russia, but it was going to happen one way or another anyway.

London is going to fall because precariarity brings a host of social problems and lawlessness. London is failing because too many empty shops deter visitors, because too many tourists can no longer afford to come, too many workers work from home, and because too many hard-pressed Londoners can’t afford to pay for it anymore. London’s local government will fail because its attempts to raise the currency it needs to repay its own borrowing simply makes London even less affordable. And it will be aided by a central government which can no longer afford to lose its tax revenues. But most of all, London is going to fail because the nominal value of all of those buildings which stores can no longer pay the rates on is nominally the “wealth” of the Marie Antoinettes who still enjoy the remnants of prosperity… As I said six years ago, we’ll see them on the other side of neoliberalism.

Banks very, very rarely lend to small business on anthing other than 100% guarantee of the Directors housing equity. Basically bankers don't even know how to ascertain if a P&L or cashflow projection is accurate and are not at all interested in fixing that.

Their sole lending criteria is based on whether they like you or not and how much equity you have in your house.

Eating the seed corn while out on a limb -- pity us all.